Tweaking the Neural Drum Machine

October 30th, 2019

TL;DR: Skip to the Neural Drum Machine section if you're only interested in how to use the drum machine

Creating, or finding drum loops can be one of the most time consuming parts of the music production process. In fact, there's an entire market out there for loopacks with drum samples, and loops from well established producers.

When I saw Tero Parviainen's codepen for a Neural Network powered drum machine, I realised that there was an opportunity to use a generative model to replace this loop hunting process. The model I had in mind would generate a seed drum sequence based on a style label. The user would then be able to edit this seed sequence, and extend it using Magenta's DrumsRNN model.

Dataset

In order to create the generative model, we first need a dataset. Luckily the Magenta group at Google has released the Groovae Dataset that contains a collection of MIDI drum loops that have been annotated with style labels

The Groovae Dataset is available through the Tensorflow Dataset API, which makes it easy to load in 2 bar and 4 bar versions of the drum loops. For this iteration of the drum machine, I ended up using the 2 bar version of the dataset.

import tensorflow as tf

import tensorflow_datasets as tfds

# Load the full GMD with MIDI only (no audio) as a tf.data.Dataset

dataset = tfds.load(

name="groove/2bar-midionly",

split=tfds.Split.TRAIN,

try_gcs=True)

# Build your input pipeline

dataset = dataset.shuffle(1024).batch(1).prefetch(

tf.data.experimental.AUTOTUNE)

Models

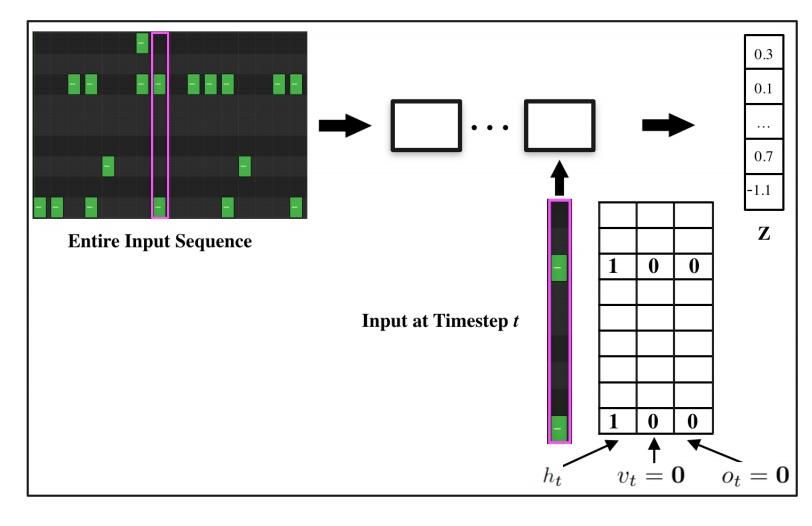

We can think of our MIDI drum data as a sequence of 9 dimensional vectors over time. In Figure 1, we see how the vertical axis represents different drum cateogories, and the horizontal axis represents time. When a drum category does not have a hit at time t the cell is filled with a 0, and when the hit is active the cell is filled with a 1.

A 2 bar sequence has 32 steps in 16th note intervals. That means we have 288 observed values (0's and 1's) that represent this sequence. If we had a 4 bar sequence, we would have 576 numbers to represent this sequence. Now instead of using more numbers to describe longer sequences, wouldn't it be great if we could just use a fixed set of numbers to represent the variations we see in these sequences regardless of length? That's where latent vectors come in.

A latent vector is just a set of numbers that contain inferred information about the observed data. We can think of them as a compressed representation of our MIDI sequence data.

If the latent space has dimensions, we can think of a single latent vector as having pieces of information about the drum sequence that we are trying to generate. For example, the first dimension of the vector describes the number of kick drum hits in the 2 bars, the second dimension describes how often those snare hits happen. Generating a drum sequence is a two step process. The first determines the attributes of the sequence that we're trying to generate and the second actually produces the sequence. 1

One way of creating latent vectors is with a Variational Autoencoder Model (VAE). An autoencoder model is a type of Neural Network that tries to predict its own input by first learning a compressed representation, i.e. a latent vector, of the data, and then reconstructing the input from this compressed representation. For a given sequence, , the VAE tries to find at least a single latent vector, , that is able to describe it. 1

We can express this process in the following way.

So what exactly is going on here? Well, given the fact that there are many potential 's that could describe our data, we're going to have to scan over the entire latent space in order to find the best candidate, which is what the integral is for. This is a computationally intractable problem, and VAE's have several clever tricks that address these issues. The most important trick is to forego optimizing the marginal likelihood , and instead optimize a lower bound on this value that is much easier to compute. This is called the Evidence Lower Bound (ELBO).

Although it may look like a lot is going on, this is a conceptually simple equation. The first term on the right hand side of the equation is a measure of how well we are able to reconstruct our input from the latent vector. The second term describes how well we are able to learn a latent space that can succinctly describe our input data.

A full explanation of the ELBO, and the various other intricacies of VAE's is out of the scope of this post. If you'd like to read more about this class of generative models, I've included some excellent articles in the references.

Anyway, back to the task at hand. I used Magenta's MusicVAE model as my encoder. The model takes in a variable length sequence of 9-dimensional vectors, representing the 9 different types of drum hits over time, and turns it into a single 256 dimension vector. I specifically chose the model with a high KL Divergence loss value. The high KL model is better at reconstructing realistic sequences from latent codes.

from magenta import music as mm

from magenta.models.music_vae import configs

from magenta.models.music_vae import TrainedModel

model_name = 'cat-drums_2bar_small'

config = configs.CONFIG_MAP[model_name]

converter = config.data_converter

model = TrainedModel(

config=config,

batch_size=1,

checkpoint_dir_or_path='../assets/cat-drums_2bar_small.hikl.tar'

)

dataset = tfds.load(name=f"groove/2bar-midionly", split=split, try_gcs=True)

dataset = dataset.shuffle(1024).batch(1).prefetch(tf.data.experimental.AUTOTUNE)

x = []

y = []

for i, features in enumerate(dataset):

midi, genre = features["midi"], features["style"]["primary"]

noteseq = mm.midi_to_note_sequence(midi.numpy()[0])

tensors = converter.to_tensors(noteseq).outputs

if tensors:

z, mu, var = model.encode(converter._to_notesequences(tensors))

onehot_label = to_categorical(

genre.numpy().reshape(-1, 1), num_classes=NUM_CLASSES

)

x.append(z[0])

y.append(onehot_label)

np.savez(

"your output path",

embeddings=x,

labels=y,

After encoding the MIDI files, we're going to have to learn a mapping between the style labels for the MIDI files, and encoded latent vectors. To do this, I'm going to use a Conditional VAE model. A conditional VAE model is a type of VAE that allows us to sample from parts of the latent space that are associated with a particular class label. So instead of maximizing the likelihood of generating a latent vector for a MIDI sequence, we're going to maximize the likelihood of generating a latent vector for a MIDI sequence with a style label as an additional input.

You can see how this changes our loss function. We will include the label in the reconstruction loss as well as the KL divergence loss.

The Neural Drum Machine

There are two ways to generate a drum sequence. The first is to select a style from the dropdown menu and click the generate button.

You can control the amount of variation in the patterns by increasing the temperature parameter.

Once you've generate a seed pattern you can modify it by clicking on the MIDI cells.You can also create a seed sequence by drawing in your MIDI pattern.

When you're satisfied with the seed sequence, you can extend it with the pink arrow button.

You can also move the position of the pink arrow in order to change the length of the generated sequences.

Once you're satisfied with the generated MIDI sequence, you can export it directly to your DAW, using a virtual MIDI bus

References

[1] https://anotherdatum.com/vae.html